July 13–31, 2023

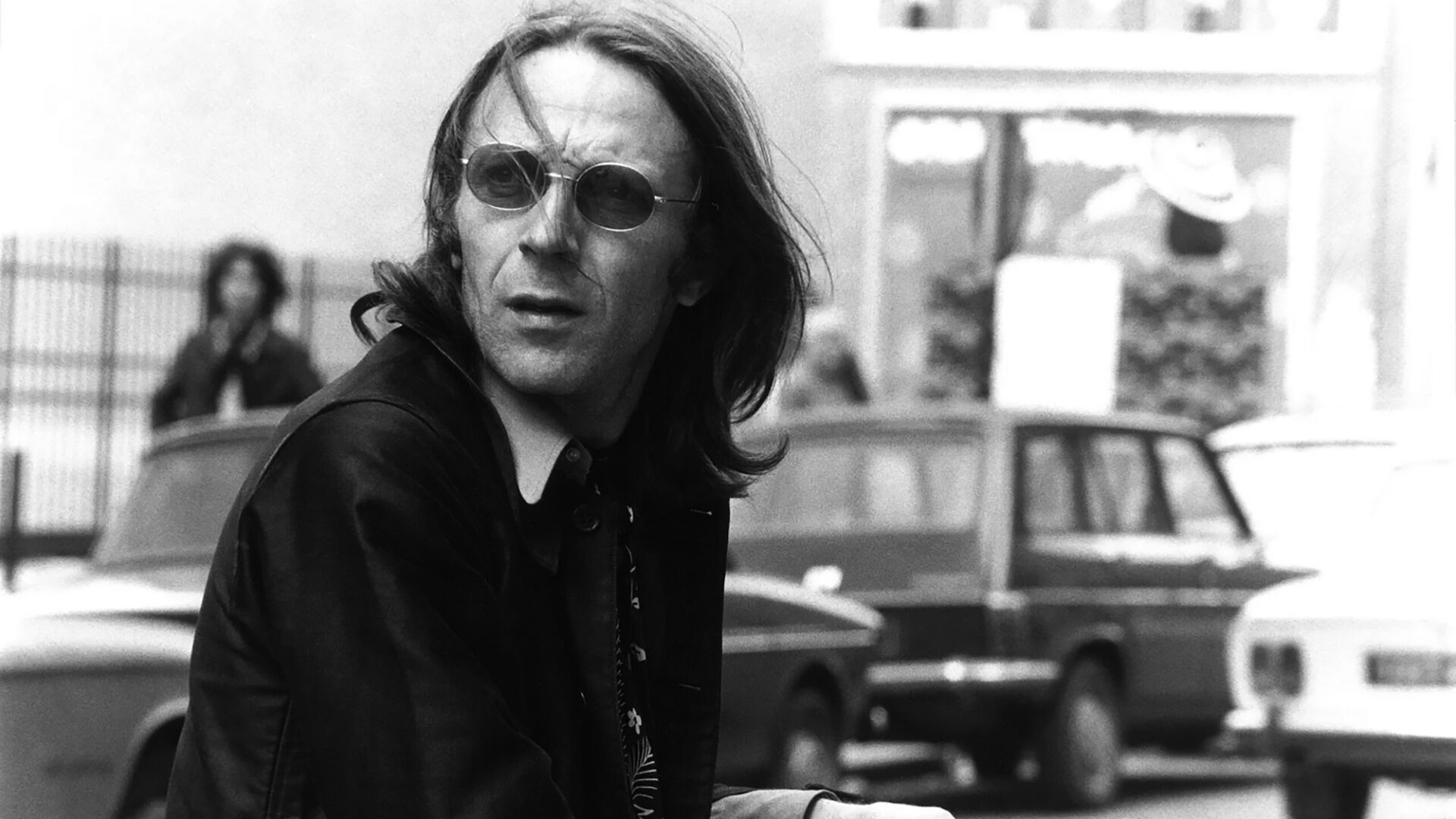

When the Camera Is On, Cinema Is Happening: The Complete Works of Jean Eustache

“One of the purest and most original directors of the contemporary French cinema.”

Nestor Almendros

Varyingly described as one of the last bastions of the nouvelle vague, one of the earliest icons of the post-New Wave, or some liminal player shuttling between the two, Jean Eustache, whatever the designation, is the legendary French filmmaker best known on our shores for his brazen three-hour-and-forty-minute opus The Mother and the Whore (1973) and appallingly little else. The reason is plain: for decades, Eustache’s catalogue has been notoriously unavailable in North America, gaining an almost mythical reputation for its outsized influence yet paradoxical invisibility. (Claire Denis, Pedro Costa, Hong Sangsoo, Jim Jarmusch are among the auteurs who have hailed its importance.) In truth, save for the exceptionally rare touring retrospective (the last was in 2001, and it skipped Vancouver) or the procuring of a bootlegged VHS, you would be hard-pressed to even see an Eustache movie without an institution ferrying a 35mm print from overseas—as we did, with a consortium of other cinemas, in 2016 for The Mother and the Whore. Until now, that is. Following Les Films du losange’s historic acquisition and remastering of the director’s entire library, The Cinematheque is honoured to present the complete works of Jean Eustache, a miracle by any measure.

Born in provincial Pessac in 1938, Jean Eustache was raised by his grandmother until his early teenage years, when he was uprooted and made to work in small-town Narbonne. (It is a chapter of his life fastidiously reenacted in his 1974 film My Little Loves.) Eventually finding his way to Paris and into the Cahiers du cinéma fraternity (his wife Jeanette Delos was the magazine’s secretary), he so impressed Jean-Luc Godard with his 1963 mid-length Robinson’s Place that JLG produced his next project and furnished the director with leftover stock from Masculin Féminin. Like that 1966 classic, Eustache’s novella-sized Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes (1967) starred New Wave poster boy Jean-Pierre Léaud and earned acclaim out of the gate, seemingly securing a paved path for its director to feature filmmaking.

But funding stalled, the industry froze him out, and Eustache turned to the economic and creative liberties of nonfiction filmmaking instead. This recourse, a reversal of the customary film-career trajectory, signalled a new telos for the artist. Drawing inspiration from the earliest actualités of the Lumières, in which the faithful recording of an event was the objective and arbiter of form, Eustache fashioned a cinema in the mold of primitive moviemaking, before the “point of departure” cleaved the medium into binaristic—and in Eustache’s view, bogus—documentary/fiction modes. His rejection of this distinction, and resolve in underscoring its arbitrariness, would be a fulcrum and distinct intellectual pleasure of his practice henceforth.

Eustache’s “neo-Lumièrian” tendencies can be traced throughout his sinuous career. They show up, most patently, in his exacting, anthropological-like portraits of rural traditions in decline: the twice-told chronicle of his birth town’s anachronistic virtue pageant (The Virgin of Pessac, 1968 & ’79); the documenting of the pre-industrial practice of hog farming in the southern highlands (Le cochon, 1970). But they also account, less obviously, perhaps, for the autobiographical nature of his work. He was, after all, “an ethnologist of his own reality” (Serge Daney, Libération), and that encompassed his personal life too. (A similar claim could be made of fellow New Wave/post-New Wave straddler Philippe Garrel.)

Nowhere is Eustache’s self-archiving impulse more apparent, or brazenly employed, than in his trio of feature films. Numéro zéro (1971), his stark full-length debut, is, on the surface, little more than an extended interview with his elderly grandmother, while his teenage sexual awakening serves as wellspring for his final long-play film, My Little Loves. Between those poles sits Eustache’s epic (and epochal) landmark: the sprawling, shocking The Mother and the Whore. Filmed in his Parisian apartment, plumbed from his own messy love life, and wielding dialogue purportedly drawn from surreptitiously recorded conversations, the director’s coup de maître administers a savage interrogation of post-1968 gender relations—and led to charges of Eustache being either a puritanical provocateur or a merciless registrar of a generation’s atrophying counterculture. A succès de scandale at Cannes and surprise recipient of its runner-up prize (despite jury president Ingrid Bergman reputedly loathing it), the film was a lightning bolt that jump-started Eustache’s mainstream credibility. The commercial failure of its follow-up, the altogether dissimilar My Little Loves, saw him banished to the margins once again. He would stay there for the remainder of his career, creating sophisticated shorts and television “documentaries” that slyly distort the thresholds between realism and reality.

In 1981, following a prolonged bout of depression and an injury in Greece that left him disabled, Eustache killed himself. He was just shy of his 43rd birthday.

“When the Camera Is On, Cinema Is Happening,” its name taken from a telling Eustache adage, offers a comprehensive survey of the august yet obscure French filmmaker’s revelatory oeuvre. The retrospective includes all 12 of the director’s newly restored films, a mélange of features, mid-lengths, shorts, and made-for-TV works, as well as Spanish filmmaker Angel Diaz’s exquisite 1997 tribute, The Wasted Breath of Jean Eustache, and speaking engagements with Thierry Garrel, who worked with Eustache at the Institut national de l’audiovisuel (INA).

Opening Night July 13 (Thursday)

6:30 pm—Wine bar with complimentary refreshments from les amis du FROMAGE

7:00 pm—50th anniversary screening of The Mother and the Whore introduced by Thierry Garrel

More Info

“The sum of Eustache’s life behind the camera, barely 15 years, needs to be recognized as more than The Mother and the Whore. It comprises an extraordinarily multifaceted collection of films, works uncompromised, completely his, devoted to the working-through of his self-reproaches and idiosyncratic little loves.” Nick Pinkerton, Moving Image Source

“He stands alone … One of cinema’s most fêted yet unfamiliar auteurs.” Martine Pierquin, Sight and Sound

“The Mother and the Whore is Eustache’s greatest cinematic achievement, though not his only significant one, as this complete retrospective proves.” Amy Taubin, Village Voice

“The French New Wave’s great bastard child … An essential retrospective.” Michael Wilmington, Chicago Tribune

Presented with the support of the Consulate General of France in Vancouver

List of Programmed Films

| Date | Film Title | Director(s) | Year | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-Jul | The Mother and the Whore | Jean Eustache | 1973 | France |

| 2023-Jul | Bad Company | Jean Eustache | ||

| 2023-Jul | Numéro zéro | Jean Eustache | 1971 | France |

| 2023-Jul | The Virgin of Pessac ’79 & ’68 | Jean Eustache | ||

| 2023-Jul | Le cochon | Jean Eustache . . . | 1970 | France |

| 2023-Jul | A Dirty Story | Jean Eustache | 1977 | France |

| 2023-Jul | My Little Loves | Jean Eustache | 1974 | France |

| 2023-Jul | Alix’s Pictures |