August 17–September 4, 2023

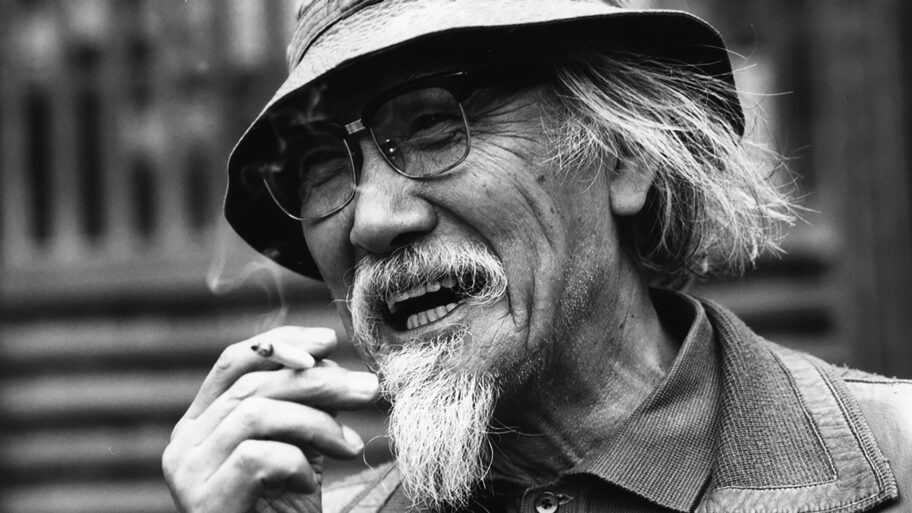

Suzuki Seijun 100

“Why make a movie about something one understands completely? I make movies about things I do not understand, but wish to.”

Suzuki Seijun

Suzuki Seijun contains multitudes. In 1991, at the first-ever North American retrospective of his films, arranged by Tony Rayns at VIFF, he was an underrated firebrand in need of discovery and canonization. At a travelling series that landed here in 2016, curator Tom Vick described Suzuki in terms of coronation, by that time the patron saint of genre acolytes Tarantino and Jarmusch. Now, on the occasion of Suzuki’s centenary and a new publication by William Carroll—the first in the English language to take all of Suzuki’s directorial works into consideration—we can say that there are still new things to see across his five decades of filmmaking.

For one, as Carroll provocatively points out, print-the-legend pronouncements have obscured Suzuki’s daring feats. “I made movies that made no sense and made no money,” a headline quote with a lot of mileage, wasn’t in fact a case of Suzuki deprecating his own work, but his recollection of a producer’s condescension. And while the non-sequitur is a powerful tool in Suzuki’s cinema, what Carroll demonstrates in Suzuki Seijun and Postwar Japanese Cinema is that its use need not detract from our appreciation of his work—there is intelligence, not just randomness, at play here.

Carroll has selected six representative films across Suzuki’s career, which the Japan Foundation has provided on 35mm prints. We’ve added six more. Only three overlap with our previous retrospective, all the better to appreciate the way Suzuki could reconfigure his modernist approach across genres and eras. When Suzuki was fired and blacklisted after the production of Branded to Kill, it wasn’t just because he was making free-associative yakuza pictures: everyone at Nikkatsu, more or less, was. Suzuki by that time had become a truly central figure, embraced by his crew (the so-called “Suzuki Group”), leftists and student activists, cinephiles, and other champions of his work. With the industry in decline the studio needed to slash costs and Suzuki was the fall guy.

That so many of his collaborators stuck with him through a fallow decade to emerge on the other side triumphant in A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness and the Taisho trilogy (presented here in full for Vancouver audiences for the first time since Rayns’s 1991 series) is a testament to Suzuki’s commitments, and an image that clashes with the lone outsider status his performance in interviews could winkingly invite.

Suzuki’s work blazed a trail that we’re only now catching up to. Consider how far his influence reaches: Suzuki Akira, his (unrelated) longtime editor, continued from strength to strength, working on and imprinting some measure of Suzuki’s tendencies on the early films of the next generation of Japanese film artists, like Itami Juzo (Tampopo) and Somai Shinji (P.P. Rider). The work of a studio filmmaker is always difficult to exhaust—absent here are his teen comedies, late musicals, and TV work—but it isn’t quantity that assures Suzuki’s place in cinema history, rather the precise reinterpretations of his films in both legends and verified sources, art and criticism.

Carroll will introduce this centenary series by video on opening night, followed by the one-two fin-de-Nikkatsu punch of Tokyo Drifter (screening on 35mm) and Branded to Kill.

“One of the giants … It’s safe to say that anyone coming to [Suzuki] for the first time will never see Japanese cinema the same way again.” Tony Rayns

“To experience a film by Japanese B‑movie visionary Seijun Suzuki is to experience Japanese cinema in all its frenzied, voluptuous excess.” Manohla Dargis

“Like those of Godard and Losey, Suzuki’s secret-agent yarns are sinister pop objects.” Fernando F. Croce, MUBI Notebook

“Suzuki never settled down … He took a flying leap with each new picture, restlessly pushing his style further and further, putting more and more pressure on it, up to and (some would say) beyond the functional breaking point.” David Chute, Film Comment

Acknowledgments

“Suzuki Seijun 100” is generously supported by the Japan Foundation, Toronto. 35mm prints of Suzuki’s films were imported and provided by the Film Library of the Japan Foundation’s headquarters in Tokyo.

Media

List of Programmed Films

| Date | Film Title | Director(s) | Year | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-Aug | Tokyo Drifter | Suzuki Seijun | 1966 | Japan |

| 2023-Aug | Branded to Kill | Suzuki Seijun | 1967 | Japan |

| 2023-Aug | Eight Hours of Terror | Suzuki Seijun | 1957 | Japan |

| 2023-Aug | Satan’s Town + Love Letter | Suzuki Seijun | ||

| 2023-Aug | Zigeunerweisen | Suzuki Seijun | 1980 | Japan |

| 2023-Aug | The Incorrigible One | Suzuki Seijun | 1963 | Japan |

| 2023-Aug | Carmen from Kawachi | Suzuki Seijun | 1966 | Japan |

| 2023-Aug | Detective Bureau 2–3: Go to Hell Bastards! | Suzuki Seijun | 1963 | Japan |

| 2023-Aug | Kagero-za | Suzuki Seijun | 1981 | Japan |

| 2023-Sep | A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness | Suzuki Seijun | 1977 | Japan |

| 2023-Sep | Yumeji | Suzuki Seijun | 1991 | Japan |