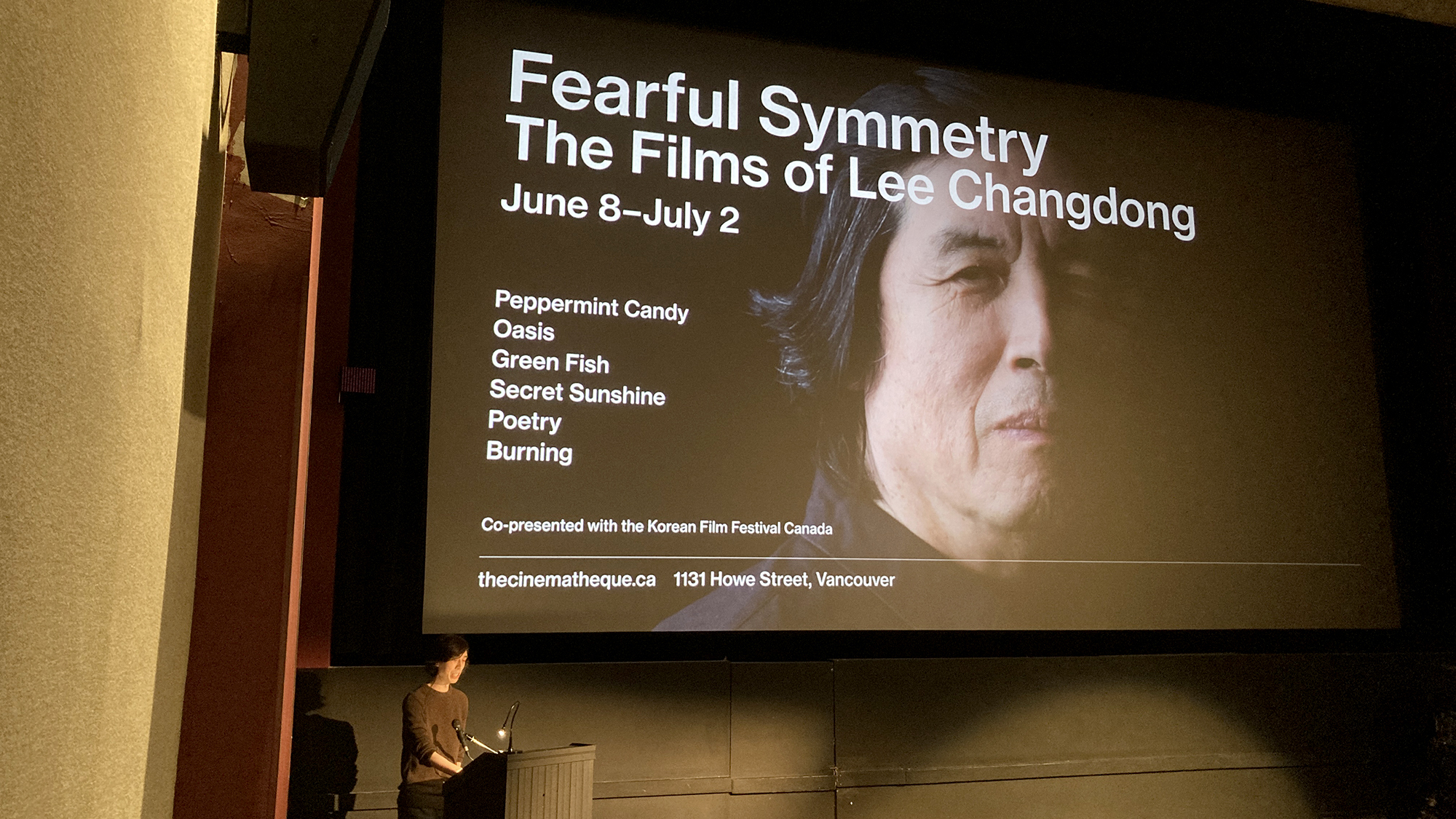

Opening Night: Lee Changdong

The Cinematheque

June 22, 2023

“Lee has the great gift of being able to combine a blistering social conscience with a formidable talent for screen storytelling.”

Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times

The June 8 screening of Peppermint Candy included the following opening remarks by Michael Scoular, The Cinematheque’s Programming Associate. The accompanying video was recorded by director Lee Changdong, and screened on the opening night of “Fearful Symmetry.”

“Good evening, and welcome to The Cinematheque for our opening night of Fearful Symmetry, a retrospective of the feature films of Lee Changdong.

Before I go any further, I first want to acknowledge that we’re on the unceded traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. The Cinematheque is grateful to gather, learn, and work in this space.

My name is Michael Scoular, I’m a programming associate here at The Cinematheque, and I’m going to talk for a few minutes to introduce the series and offer a thought or two before the film. I want to thank everyone for coming out tonight, and I especially want to recognize this series’ co-presenter, the Korean Film Festival Canada, without whom this program would not be happening, at least not in the same way. As a programmer here, I get to see ideas for retrospectives that never see the light of day, or are delayed because of a number of factors: the availability of prints and digital materials, distribution patterns, costs and so on, and this series went very quickly from being an incomplete idea to fully realized thanks in part to the Korean Film Festival Canada and its Artistic and Executive Director Mi-Jeong Lee. So thank you to the organization, and thank you Mi-Jeong.

I’d also like to welcome our guests from the Consulate General of the Republic of Korea in Vancouver, and from the Korean community who are with us tonight.

Now as for the films, I don’t plan to speak to what they’re about or how acclaimed they are. If you’re here tonight, you already know in some way that there’s something worthwhile about seeing Lee’s films. I guess I’m more interested in talking about approaches. How does Lee approach cinema, and how can we approach his films.

Lee has often returned to stories about his first encounters with film. I think they’re revealing, at least to the extent that any well-practiced interview anecdote can be. In the one I’m going to focus on tonight, Lee tells of how, before he’d seen any films, he first participated in the making of one. The Korean social drama Sorrow Even Up in Heaven, a neorealist parable about a young, impoverished boy, his talent for writing, and his exploitation, was partially filmed at the elementary school Lee was attending at the time.

On the weekend, like any neighbourhood kid, he came to watch and participate in any way he could. He was told that if he could bring an umbrella, he could be an extra in a scene. He ran home, and grabbed a new one, and when he arrived back on the set, the propmaster slashed and distressed the umbrella before inviting Lee to join a line of children who would walk, in the background of a shot, through a torrent of rain.

Now it’s possible that this experience was traumatic for Lee or perhaps it made him feel self-conscious about his own family’s precarious existence. (After all, he was born into a family of six children, with only one working parent.) What I find intriguing about the story, though, is that it shows Lee understood from a young age that even when the cinema comes closest to replicating lived experience, it still relies upon a certain amount of illusion.

Lee never attended film school, but even after achieving some success as a writer, he became convinced that in order to be an artist whose work mattered, he needed to be able to address an audience as broad and unspecialized as the one that attends movies. You could say that he believed in the idea that an artist has a duty to their public, and in a country like South Korea, where a quota system ensures Korean cinema has a place in Korean theatres, this need not amount to a far-fetched theory or a narcissistic fantasy.

Peppermint Candy, Lee’s second feature, seems to exemplify this motivation. I’m going to talk about the film without giving away any of its specific plot details, since I imagine there are people here who haven’t seen the film before, so please bear with me. Peppermint Candy was released on New Year’s Day 2000 in Korean cinemas, and Lee has mentioned that talk of the new millennium was unavoidable when he first sketched out the idea for the film. People were both anxious and hopeful, but regardless of how they felt, their attention was pointed towards the future. Lee’s response was to turn the other way round, and make a film concerned with the past.

But there is another side to Lee. I think Lee Changdong is the only popular narrative filmmaker that I’ve heard use the term ontology in an interview—despite his distance from academia, he’s not opposed to theory, in fact he’s a theorist of a kind himself.

By making a film concerned with the past, I do think that Lee is doing something quite different from what some appreciative critics find in Peppermint Candy. Dazzled by its structure and use of history, they have read the film as either a national allegory or an attempt to redeem its protagonist through the progressive unveiling of his past history. Neither of these accounts get at how Lee uses illusion to arrive at something like real life—which is different from realism—in art.

When he uses the past in Peppermint Candy, there’s a fundamental question we need to ask ourselves about how we understand the reality of time. Is what we are seeing flashbacks? A flashback, of course, traces a circuit from the present to the past before returning back to the present with a new kind of awareness. That, I think, is not quite how Peppermint Candy works. Lee has said, on the other hand, that the model of time that was most on his mind while making the film was Proust’s—and even if we don’t grant him that lofty connection, at the very least, we might notice that there’s something strange about the way this film moves through the past. There is no past outside of the character to flash back to, but different layers of the past for him to enter, each one both more mysterious and simpler than the one that precedes it—while it might sound ridiculous, it’s possible the protagonist in Peppermint Candy is, through Lee’s interventions, time travelling in much the same way as the protagonist in Alain Resnais’s Je t’aime, je t’aime.

While I am setting up a certain type of reading here—one that I think is useful for understanding what’s happening in some of Lee’s other works, particularly Poetry—Peppermint Candy is ultimately a film open enough to support many approaches. I hope you find it a rewarding experience, and that, if you feel so inclined, you see some of Lee’s other films while they’re playing in this retrospective.

Lee has contributed a welcome message addressed to the Korean Film Festival Canada that will now play, and after that the feature Peppermint Candy will begin. Thank you for listening.”